Pope Paul VI Canonised - Is Humanae Vitae the only Story?

The canonisation of Pope Paul VI (1963-1978) on 14 October 2018 came only months after the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Humanae Vitae (29 July 1968), the encyclical for which he is best and most controversially known, and after the fortieth anniversary of his death (6 August 1978). What kind of man was this pope? What did his time as a pope mean for the Church?

Ordained priest without having attended a seminary, Giovanni Battista Montini proved to be a successful and pioneering Archbishop of Milan without having ever been a parish priest. A prelate who decried John XXIII’s calling of a council, would go on to guide Vatican II so skilfully and sensitively that it concluded its deliberations without division and in a spirit of enthusiastic hope. The complexities of his personality and his ministry are clear and, perhaps, puzzling. Described by his biographer, Peter Hebblethwaite, as ‘The First Modern Pope’, Paul VI initiated a series of papal visits outside Rome that creatively furthered the process of updating or aggiornamento on which his predecessor had launched the Church. These visits also had profound ecumenical meaning.

Aggiornamento and ecumenical advance were particularly prominent in the first of his trips. A month after closing the second session of the Council (the first session during his papacy), he travelled to the Holy Land, to walk where Jesus walked and taught, and to venerate the site of his Passion. While he was there, he and Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I had the first meeting of a pope and patriarch since the schism of 1054. Their meeting on the feast of the Epiphany reminded the various traditions in the Christian world of the need to support one another in our shared commitment to the Beloved Son of God and of our shared duty to listen to him. The meeting opened the way to the mutual lifting of the excommunications of 1054. The document implementing this, signed by both pope and patriarch, was read out simultaneously on 7 December 1965, during the final session of the Council in Rome and in the patriarchal church in Constantinople.

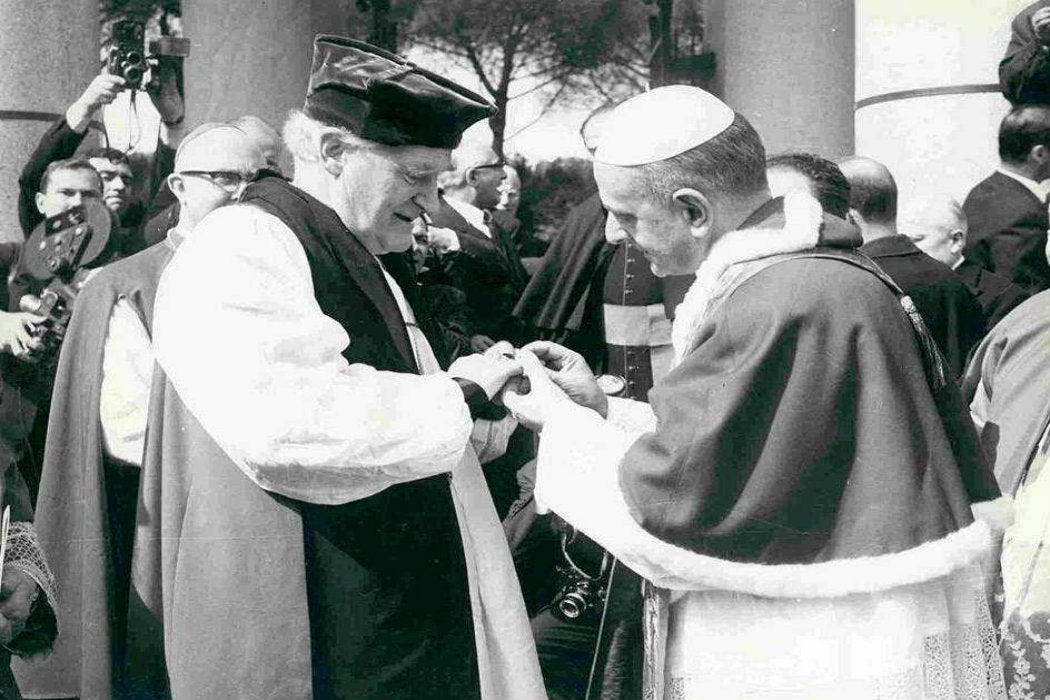

Image: The first meeting between Pope and Ecumenical Patriarch: Paul VI and Athenagoras I

Pope Paul’s exceptional flair for devising significant opportunities to advance both aggiornamento and ecumenism manifested itself again some months later, when he received Archbishop Michael Ramsey of Canterbury on a formal visit to the Vatican and they presided together over a prayer service in the Sistine Chapel. The image of the two pastors, seated side by side in front of the altar, with Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgement’ towering over them, was an eloquent expression of their joint commitment to addressing the scandal of Christian disunity. It was also on this visit that Pope Paul removed his own ring, to place it on Archbishop Michael’s hand. That first formal public meeting between a serving pope and an Archbishop of Canterbury led to the founding of the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission and the opening of the Anglican Centre in Rome.

The publication, in July 1968, of the encyclical Humanae Vitae did not receive the same acclaim as Pope Paul’s visits to the Holy Land or to the United Nations, or his encyclical on development, Populorum Progression (1967), or the welcome he gave to the Archbishop of Canterbury. The difficult reception of the encyclical on the regulation of birth was due to a number of factors. Probably the most prominent were the fact that an expectation of change in received teaching on artificial family planning had grown up among Catholics, and that the summer of the student protests all over Europe was not a time auspicious to receiving an unwelcome teaching.

The novel The British Museum Is Falling down, by David Lodge, gives an amusing and poignant account of the life of a young Catholic couple in 1965 hoping for a change in papal teaching on family planning.

In the real world, information was emerging from the Pontifical Commission for the Study of Population, Family and Births – more often referred to as the Birth Control Commission. Set up by Pope John XXIII when he withheld the topic of family planning from consideration by the Council, it had been strengthened by Pope Paul who expanded its membership to include married people. Among the new members were an American married couple who surveyed 3,000 practising Catholics from 18 countries on how using the rhythm method affected their marriages. Overwhelmingly, they reported that it had a bad psychological effect, that it did not contribute to marital unity, and that it was unnatural. On 3 June 1966, the bishops and theologians on the commission agreed unanimously on four points: that contraception is not intrinsically evil; that the 1930 encyclical Casti Connubii is not irreformable; that the Church was in a state of doubt; and that it could change its position. The Commission concluded that the prevailing Catholic teaching on artificial contraception ‘could not be sustained by reasoned argument’.

For two years after this report had been submitted, the Pope pondered what to do. During that time, Peter Hebblethwaite reveals in his book, Pope Paul VI, The First Modern Pope, Pope Paul gave less credence to the report of his own commission than to papers advising him that a change would undermine papal authority. Although he was impressed by the report and was attracted by its conclusions, the Pope eventually went along with arguments put to him by Fr John Ford, S.J., Fr Ermenegledo Lio, O.F.M., and Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani. The book Love and Responsibility, by Archbishop Wojtyla of Krakow, published in Polish in 1960 and in French in 1965, may also have influenced the writing of Humanae Vitae. Archbishop Wojtyla, though a full member of the Commission, did not attend the final, decisive meetings.

If Pope John and Pope Paul had not prevented the Council from discussing family planning, would a conciliar document have won wider acceptance? It’s impossible to say. And the example of the divisions occasioned within the Anglican Communion by the debates on sexuality at the Lambeth Conference of 1998 should be heeded. But such worries need not be decisive. Just as the conciliar process proved productive on such controverted questions as liturgical change and an opening to ecumenism, there are sound reasons for thinking that trusting the process could have been helpful when renewing Church teaching on family matters – as the example of Evangelii Nuntiandi suggests.

In the 1970s, Pope Paul re-discovered a voice which carried conviction. The Synod of Bishops on Evangelisation (1974) rejected the final report on its debates prepared by its relator, Cardinal Wojtyla, as not representing what had been discussed: in fact, the future Pope had written the document with the help of a Krakow theologian during his summer holidays before the Synod had even opened. As a result of the report being rejected, it fell to Pope Paul to receive all the documents of the Synod and to sort the matter out. His response was the magnificent Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi (1975). Peter Hebblethwaite describes this document (p. 651) as ‘at once both synodal and papal, and therefore deeply collegial.… It was a new way of relating to the Church, a novel and more effective form of the magisterium.’

Bernard Treacy, O.P.

Based on an editorial in Doctrine & Life, September 2008